Writing Objective-C iOS apps without Storyboards

TL;DR: This article explores how to write iOS applications with Objective-C without making use of traditional Storyboards

My team supports the foundations for building a desktop application: Postman. In the interest of supporting the application in all the platforms its users are on, I have been researching the feasibility of porting the native desktop framework we have to platforms like mobile.

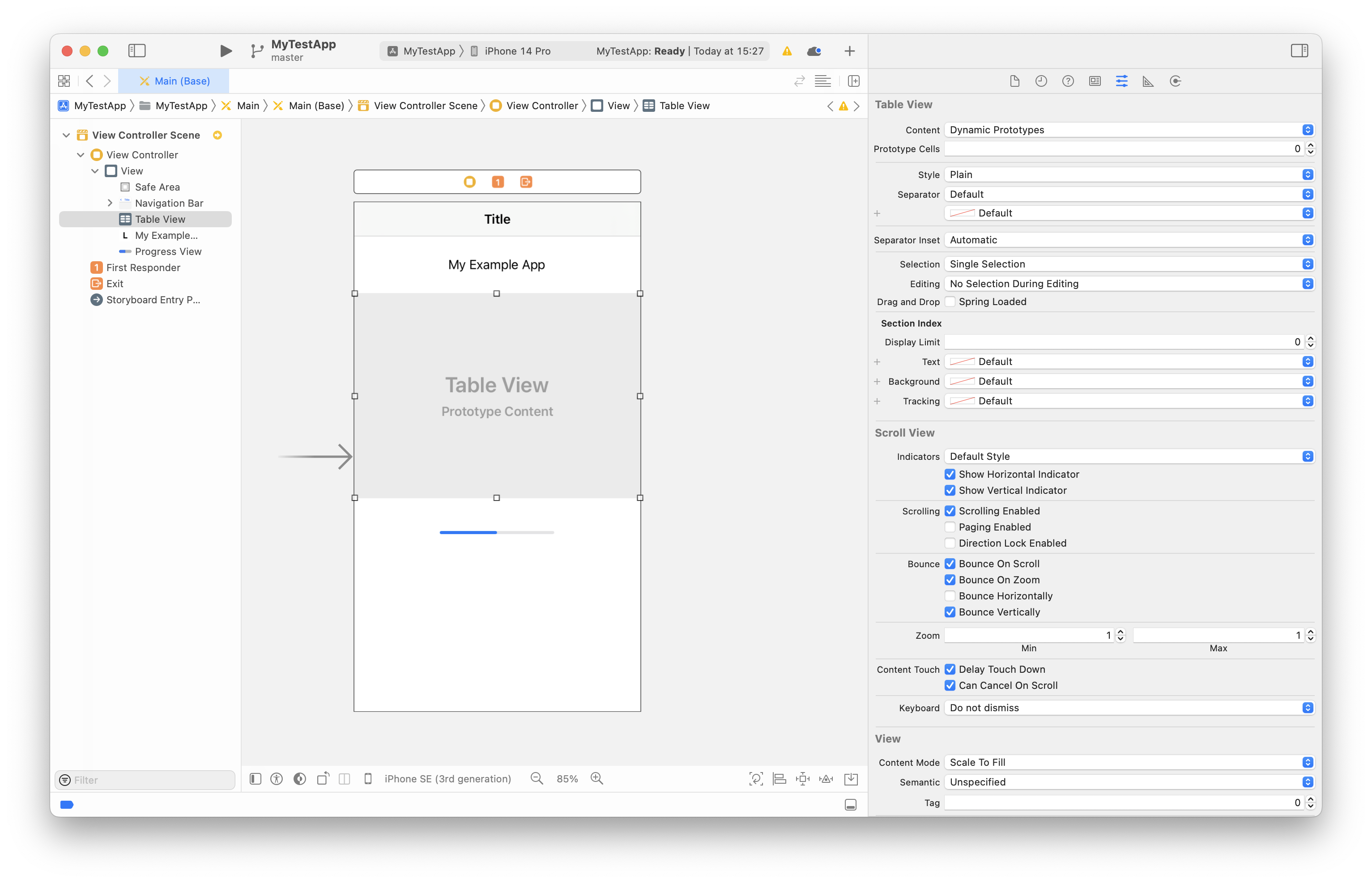

As a progression of the visual UI design paradigm introduced by Interface Builder, Apple introduced Storyboards for developers to visually create iOS views and make connections between them. iOS applications typically use Storyboards for both the launch screen and the user interface. Storyboards are useful for building iOS applications while writing minimal code. However, any edit to a Storyboard requires the Xcode IDE and as a consequence, it is impractical to review changes to Storyboards under version control. This is a example of a Storyboard in Xcode:

While Apple heavily pushes for Swift, Objective-C still has its place on projects that demand smoother interoperability with C++. However, most modern resources out there exclusively focus on Swift, making it difficult to get started.

This article makes use of Xcode 14.1 (14B47b) running on macOS Ventura 13.1 on a 2020 M1 MacBook Pro, targeting iOS 16.1 on an iPhone 14 Pro simulator.

The entry point and the application delegate

iOS applications declare a main entry point that

passes control to the UIKit

framework through the UIApplicationMain

function. This function assigns a delegate object to manage the

life cycle of the application. It typically looks something like

this:

// main.m

@import UIKit;

#import "AppDelegate.h"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

@autoreleasepool {

return UIApplicationMain(argc, argv, nil,

NSStringFromClass([AppDelegate class]));

}

}The fourth argument to UIApplicationMain

determines the application delegate. In this case, it is the

class named AppDelegate, defined in the

AppDelegate.h header that we are importing at the

top of the file.

The application delegate class is an instance of UIResponder

(a base class for event handlers) that implements the UIApplicationDelegate

protocol. The core responsibilities of an application delegate

is to create and manage the top-level UIWindow

object. When UIKit

takes over through the UIApplicationMain

function, it will create an instance of the application delegate

and eventually call its application:didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:

method. We override this method as the place to programmatically

create the application window.

The AppDelegate class declaration looks

something like this:

// AppDelegate.h

@import UIKit;

@interface AppDelegate : UIResponder <UIApplicationDelegate>

@property(strong, nonatomic) UIWindow *window;

@endIts corresponding definition instantiates the UIWindow

property using the device screen bounds as its frame.

// AppDelegate.m

#import "AppDelegate.h"

@implementation AppDelegate

- (BOOL)application:(UIApplication *)application

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:(NSDictionary *)launchOptions {

self.window = [[UIWindow alloc] initWithFrame:[[UIScreen mainScreen] bounds]];

return YES;

}

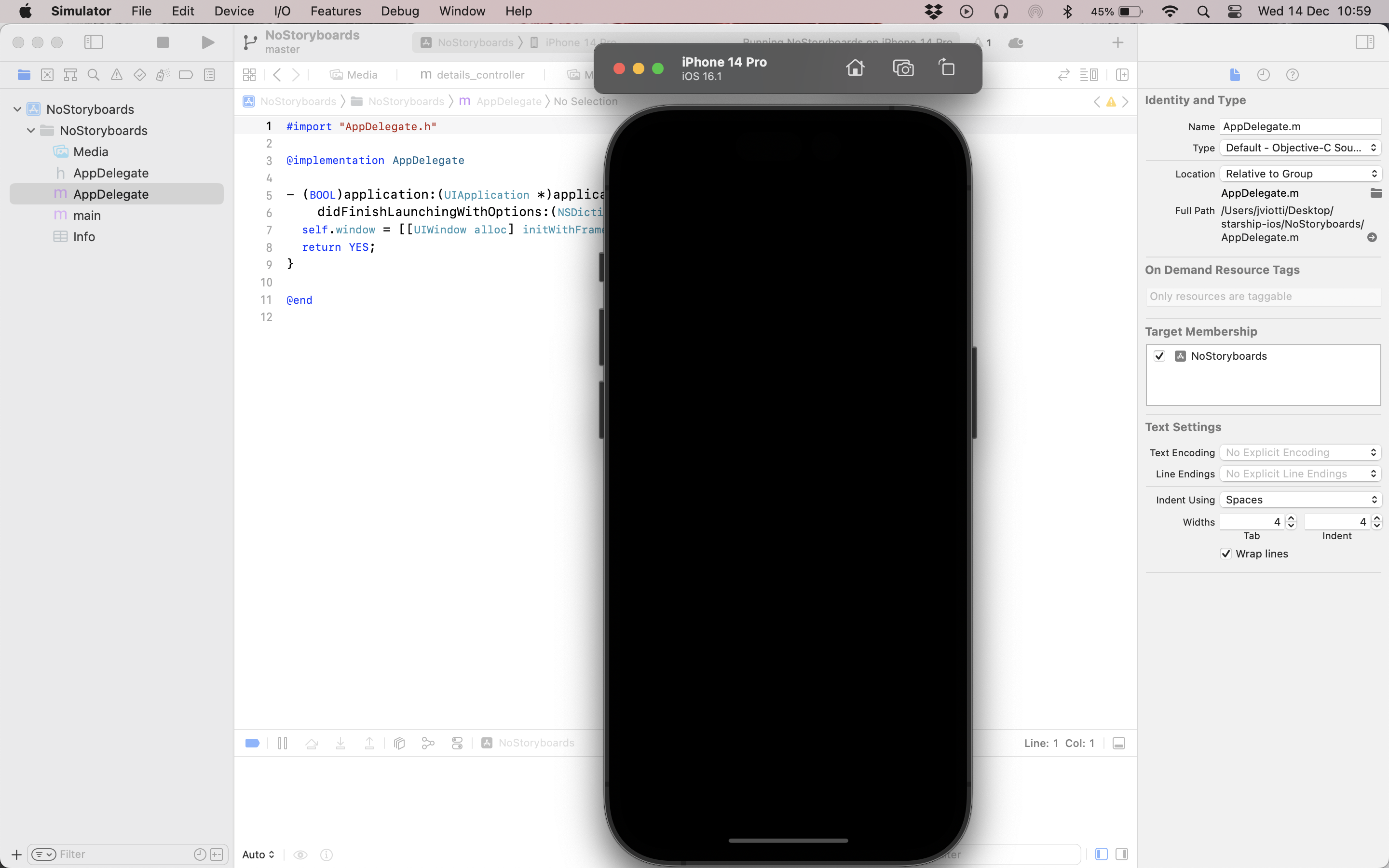

@endAt this point, the application will compile and run. However, you will only see a black window.

Adding a navigation controller

Most multi-view iOS applications provide a stack-based scheme

for switching between views. Under this scheme, the application

shows a title bar at the top, provides animated transitions

between views, provides a “Back” button for going back to the

previous view and more. On UIKit,

the class that implements these behaviors is UINavigationController.

Without Storyboards, our AppDelegate class will

instantiate the navigation controller, set it as the root view

controller of the window and display the window. It would look

something like this:

// AppDelegate.m

...

- (BOOL)application:(UIApplication *)application

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:(NSDictionary *)launchOptions {

self.window = [[UIWindow alloc] initWithFrame:[[UIScreen mainScreen] bounds]];

UINavigationController *navigation_controller =

[[UINavigationController alloc]

initWithRootViewController:????

[self.window setRootViewController:navigation_controller];

[self.window makeKeyAndVisible];

return YES;

}

...However, the initWithRootViewController:

initializer method of UINavigationController

requires a reference to a view controller that will be pushed as

the first element of the navigation stack. This view controller

will represent the first screen of our application.

The first view controller

In UIKit,

view controllers subclass from UIViewController.

As their name implies, the responsibility of a view controller

is to create and manage a view represented by the UIView

class. For performance reasons, view controllers lazily create

their corresponding UIView

properties when the loadView

method is invoked. Following this lazy-loading style, the

initialization logic of a view controller is done when the viewDidLoad

method is invoked.

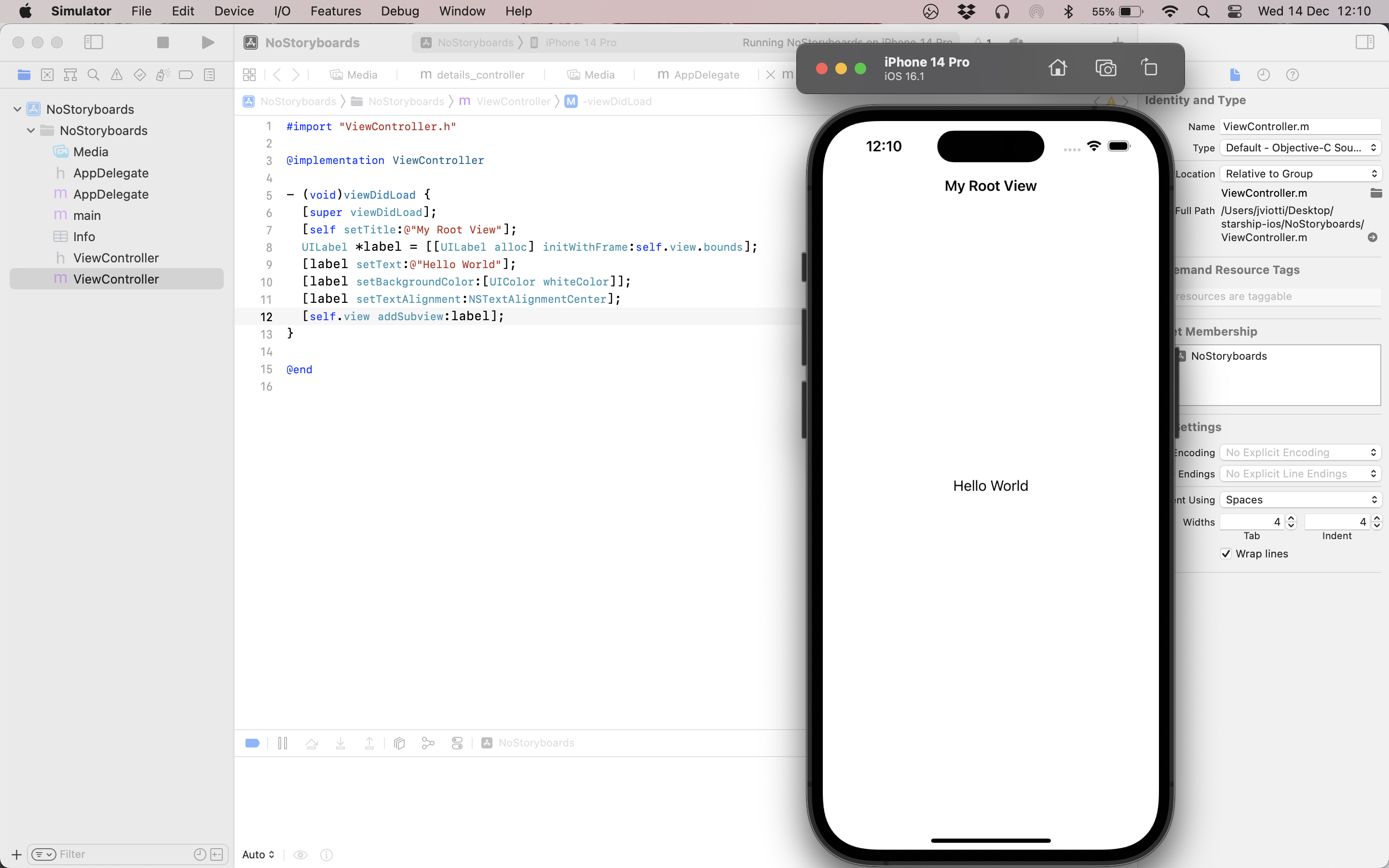

To start with, we will create a simple view controller that shows a label on the screen.

// ViewController.h

@import UIKit;

@interface ViewController : UIViewController

@endThe class definition overwrites the loadView

method to instantiate a UILabel

and overwrites the viewDidLoad

to update the view title. Every view controller managed by a

navigation controller has access to a title

property that affects the string rendered in the navigation bar.

In this case, we set it to “My Root View”.

#import "ViewController.h"

@implementation ViewController

- (void)loadView {

[super loadView];

UILabel *label = [[UILabel alloc] initWithFrame:self.view.bounds];

[label setText:@"Hello World"];

[label setBackgroundColor:[UIColor systemBackgroundColor]];

[label setTextAlignment:NSTextAlignmentCenter];

self.view = label;

}

- (void)viewDidLoad {

[super viewDidLoad];

[self setTitle:@"My Root View"];

}

@endNow that we have a view controller, we can use it to

correctly instantiate our navigation controller on the

AppDelegate class.

#import "AppDelegate.h"

#import "ViewController.h"

@implementation AppDelegate

- (BOOL)application:(UIApplication *)application

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:(NSDictionary *)launchOptions {

self.window = [[UIWindow alloc] initWithFrame:[[UIScreen mainScreen] bounds]];

ViewController *view_controller = [[ViewController alloc] init];

UINavigationController *navigation_controller =

[[UINavigationController alloc]

initWithRootViewController:view_controller];

[self.window setRootViewController:navigation_controller];

[self.window makeKeyAndVisible];

return YES;

}

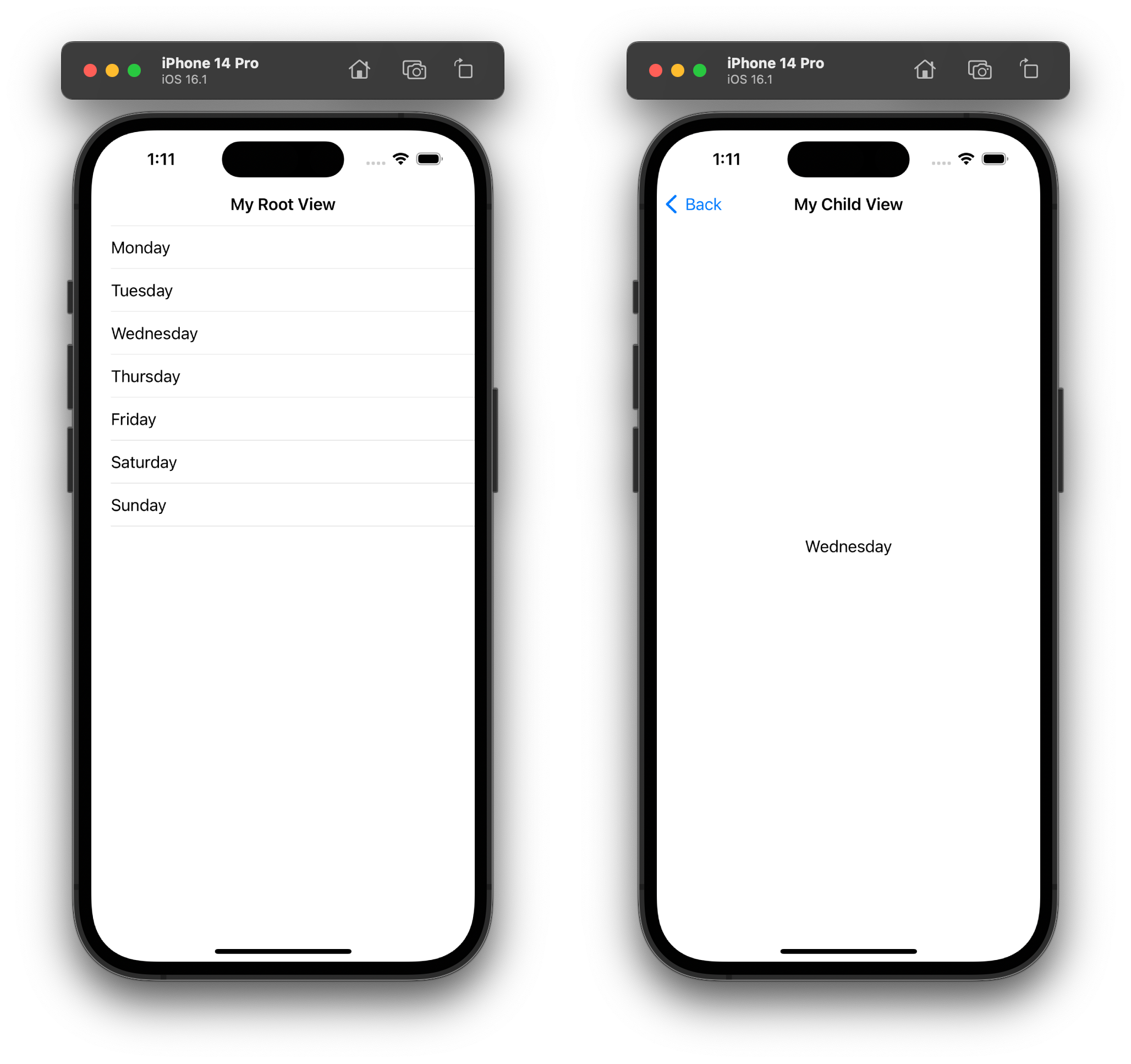

@endIf you run the application again, you will see a title bar followed by our label.

Adding a table view

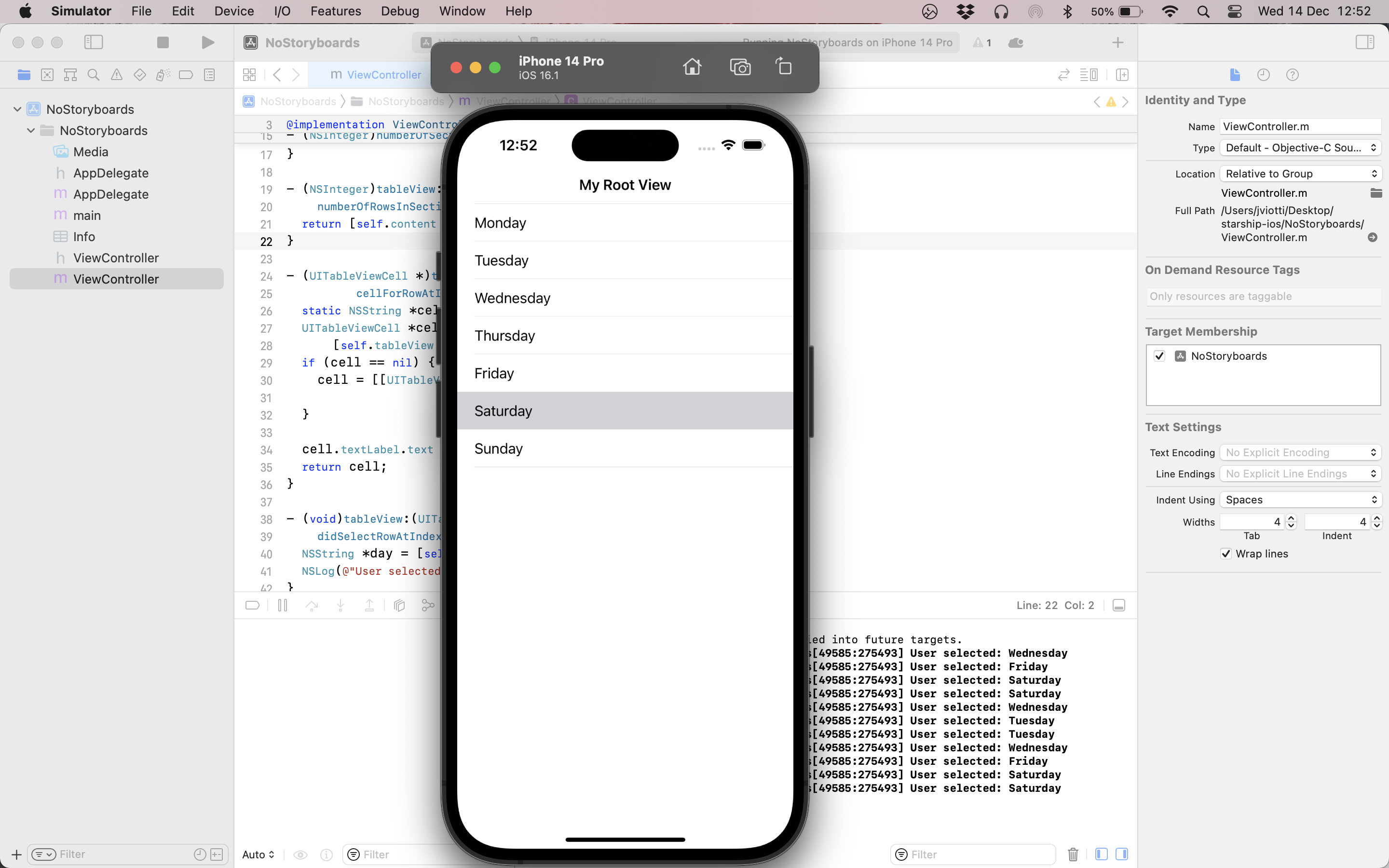

Before we add another view to our application, let’s make the initial view slightly more interesting than just a static label: a table that lists the days in a week.

In UIKit,

tables are implemented using the UITableView

class. The complementary UITableViewController

class does an excellent job abstracting away the gory details of

managing a table in a performant manner. This class

automatically instantiates a UITableView

as a property called tableView,

and makes the controller act as the data source and delegate of

the table through the UITableViewDataSource

and UITableViewDelegate

protocols, respectively. In terms of our example table, the

former protocol allows us to manage the table contents and the

latter protocol allows us to respond to table selections.

First, we will update our ViewController

declaration to inherit from UITableViewController

and declare an array property to keep track of the table

content.

// ViewController.h

@import UIKit;

@interface ViewController : UITableViewController

@property(strong, nonatomic) NSArray *content;

@endFor the class definition, we will start by getting rid of the

loadView

override, given that UITableViewController

will manage this for us, and we will instantiate the

content property on the viewDidLoad

method.

// ViewController.m

#import "ViewController.h"

@implementation ViewController

- (void)viewDidLoad {

[super viewDidLoad];

[self setTitle:@"My Root View"];

self.content = @[

@"Monday", @"Tuesday", @"Wednesday", @"Thursday", @"Friday", @"Saturday",

@"Sunday"

];

}

@endThen, we will implement a set of new methods that are part of

the UITableViewDataSource

and UITableViewDelegate

protocols:

numberOfSectionsInTableView:. To configure the number of sections in the table. In this case, we will only have one section.tableView:numberOfRowsInSection:. The configure the number of rows the table should display for every section. We only have one section and the number of rows is equivalent to the size of thecontentarray.tableView:cellForRowAtIndexPath:. To populate the content of each table cell. TheNSIndexPathinstance corresponds to the cell coordinates in terms of their section and row. This implementation makes use of thedequeueReusableCellWithIdentifier:method ofUITableViewto re-use already allocated cells when possible instead of creating new ones every time.tableView:didSelectRowAtIndexPath:. To handle taps to specific rows. We will only log the user selection to the console for the time being.

// ViewController.m

...

- (NSInteger)numberOfSectionsInTableView:(UITableView *)tableView {

return 1;

}

- (NSInteger)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView

numberOfRowsInSection:(NSInteger)section {

return [self.content count];

}

- (UITableViewCell *)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView

cellForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath {

static NSString *cellIdentifier = @"my-table";

UITableViewCell *cell =

[self.tableView dequeueReusableCellWithIdentifier:cellIdentifier];

if (cell == nil) {

cell = [[UITableViewCell alloc] initWithStyle:UITableViewCellStyleDefault

reuseIdentifier:cellIdentifier];

}

cell.textLabel.text = [self.content objectAtIndex:indexPath.row];

return cell;

}

- (void)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView

didSelectRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath {

NSString *day = [self.content objectAtIndex:indexPath.row];

NSLog(@"User selected: %@", day);

}

...If you run the application, you will see a table of 7 elements. Tapping into each row will print a line to the console.

Adding a new view

Let’s recycle the example label view we had before we

introduced the table to render a basic view whenever the user

selects a row in the table. The mechanics are what you would

expect: we subclass from UIViewController,

and override loadView

and viewDidLoad.

Additionally, we will implement an initializer that takes the

string that the view should display.

// DetailsController.h

@import UIKit;

@interface DetailsController : UIViewController

@property(strong, nonatomic) NSString *content;

- (id)initWithText:(NSString *)details;

@endBecause of UIKit’s auto-layout feature, we don’t need to accurately pass the right frame to the label view. We can pass an “empty” frame and it will be auto-resized to fit the available space. Notice that we change the navigation title to “My Child View”.

// DetailsController.m

#import "DetailsController.h"

@implementation DetailsController

- (id)initWithText:(NSString *)details {

self = [super init];

[self setContent:details];

return self;

}

- (void)loadView {

[super loadView];

UILabel *label = [[UILabel alloc] initWithFrame:CGRectMake(0, 0, 0, 0)];

[label setText:self.content];

[label setBackgroundColor:[UIColor whiteColor]];

[label setTextAlignment:NSTextAlignmentCenter];

self.view = label;

}

- (void)viewDidLoad {

[super viewDidLoad];

[self setTitle:@"My Child View"];

}

@endMaking use of this new controller is trivial. First, we will

import it on the ViewController implementation:

// ViewController.m

#import "ViewController.h"

#import "DetailsController.h"

@implementation ViewController

...Then, we will update the tableView:didSelectRowAtIndexPath:

method to show the controller instead of logging the user

selection to the console. Every view controller has access to a

showViewController:sender:

method that pushes another view controller to the navigation

stack.

- (void)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView

didSelectRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath {

NSString *day = [self.content objectAtIndex:indexPath.row];

[self showViewController:[[DetailsController alloc] initWithText:day]

sender:self];

}If you run the application and tap in a table row, the details view will slide in. The navigation bar will automatically display a “Back” button to get back to the table view.

Setting a launch screen

iOS launch screens are also typically implemented using

Storyboards. However, Apple provides a basic mechanism to define

launch screens at the Info.plist

level through the UILaunchScreen

key. This feature is not as comprehensive as Storyboards, but it

is enough to define basic launch screens with a background color

and an image.

Make sure that you remove the UILaunchStoryboardName

key first, if any.

The sub-properties defined in the UILaunchScreen

key must refer to resources stored inside an asset catalog, so

make sure you have one before you continue. You can create one

through “File -> New -> File…” and selecting “Asset

Catalog” from the “iOS” category. I will name it “Media”, but

you can choose any name you want. The catalog will contain two

things: a “Color Set” for the background color and an “Image

Set” for the image.

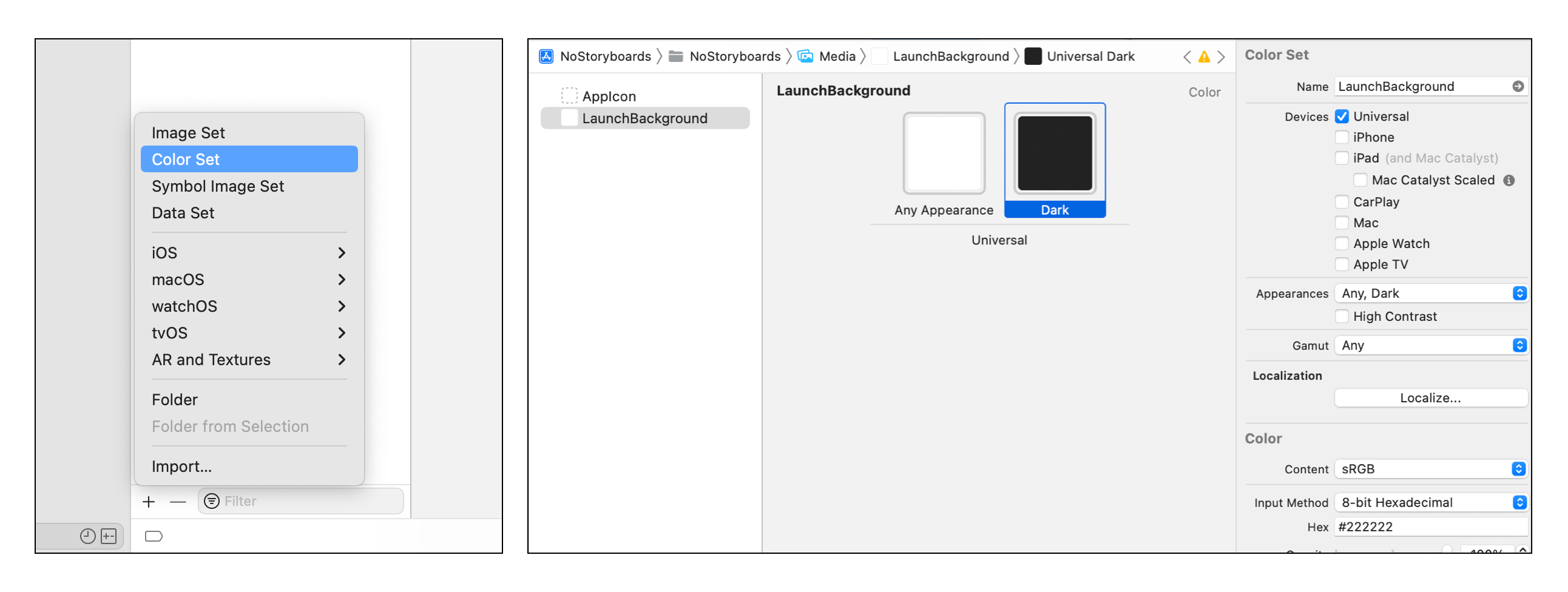

Creating a color set

We will create a Color Set named

LaunchBackground. You can do so from the bottom

plus sign on the asset catalog navigator. You can click on both

squares to select a background color for the light and dark

themes. I will go for #fff and #222,

respectively.

We named the color set LaunchBackground, so we

will set the UIColorName

key in the Info.plist accordingly.

<key>UILaunchScreen</key>

<dict>

<key>UIColorName</key>

<string>LaunchBackground</string>

</dict>Creating an image set

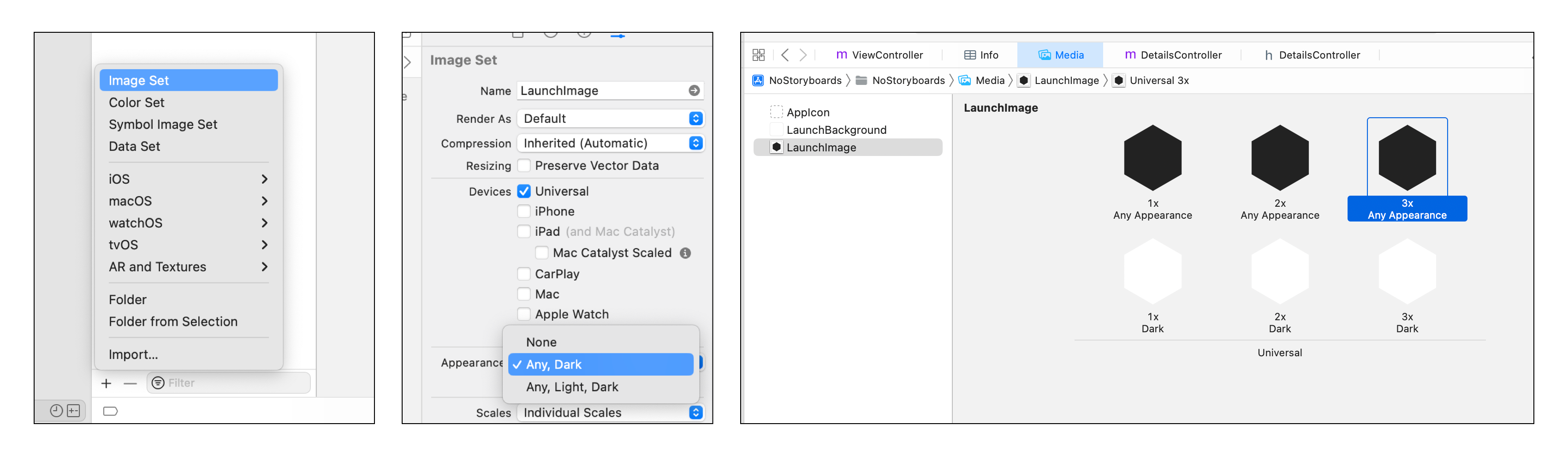

In the same way, we will create an Image Set named

LaunchImage. Under the Attribute Inspector pane at

the right, we will go to the Appearance section and enable dark

mode support by selecting “Any, Dark” from the dropdown. Then,

we will place the desired launch images to the corresponding

squares. For the sake of the example, I created simple black and

white hexagons.

We named the image set LaunchImage, so we will

set the UIImageName

key in the Info.plist accordingly. We will also

turn on UIImageRespectsSafeAreaInsets

to force the image to fit in the safe area of the launch

screen.

<key>UILaunchScreen</key>

<dict>

<key>UIColorName</key>

<string>LaunchBackground</string>

<key>UIImageName</key>

<string>LaunchImage</string>

<key>UIImageRespectsSafeAreaInsets</key>

<true/>

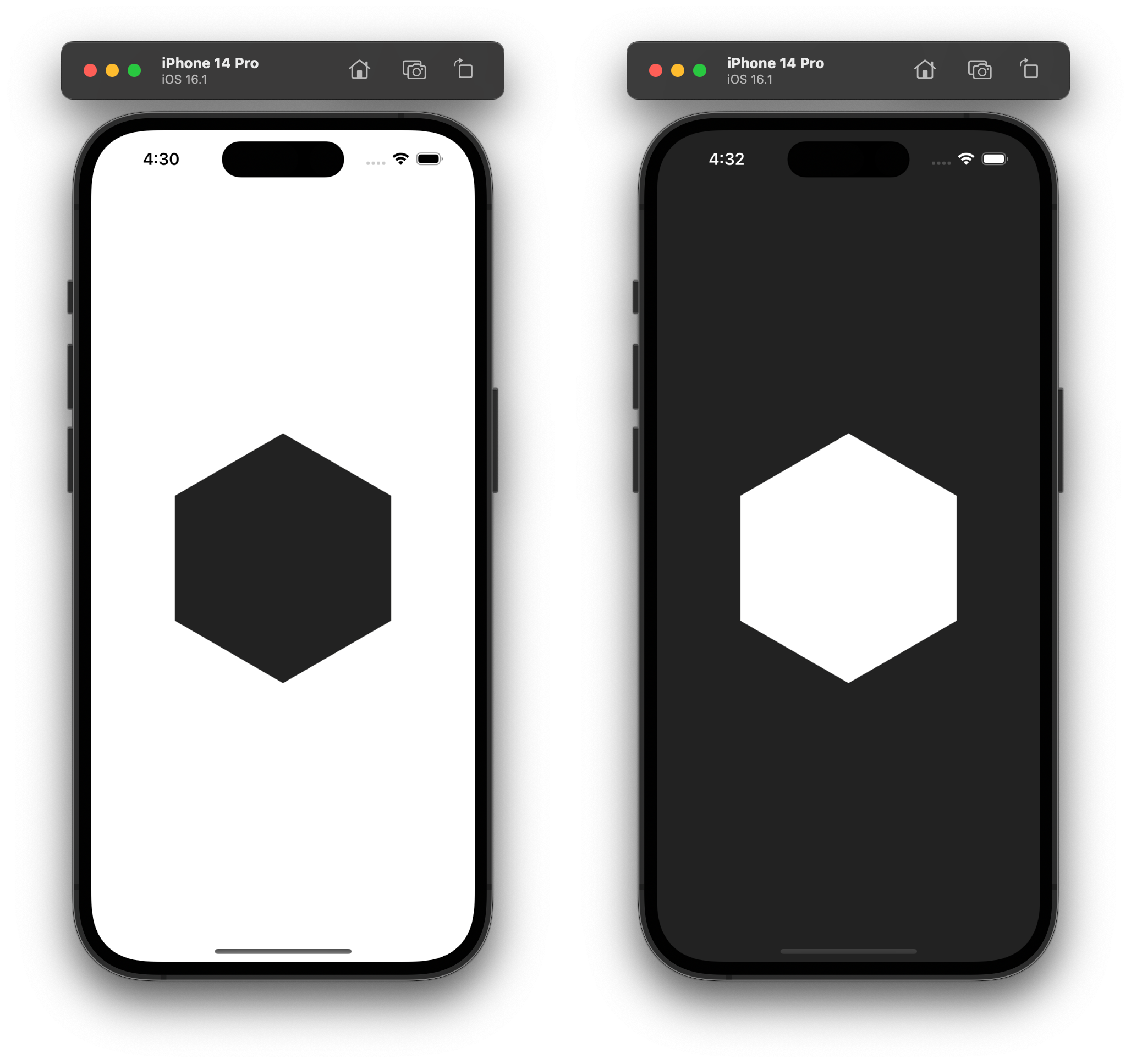

</dict>If you run the application once more, you will see the color set and the image set being displayed according to the theme configuration.

Getting the code

The Xcode project corresponding to this example can be downloaded here: NoStoryboards.zip. The code is licensed under the CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication. You are welcome to use it as a basis for any project without requiring attribution.